BILL'S [Somewhat] WEEKLY COLUMN/BLOG PAGE

THAT INSANE 1973 UP HERE

1973 was a memorable year for me in a lot of ways. My twins were born; my sign

business was really taking off; I got a decent raise at school; and, of course

there was that faked – up &*^%#ed - up energy crisis BS we were subjected to.

But, all that notwithstanding, the earlier months came about with the promise of

Beaver Dragon's Country Dollar #75 team, having quickly tired of the car they

bought the previous season, finishing the build on their own late model

sportsman.

Beaver was a good friend, by 1973. I taught with his wife, Jane and we had the same babysitter for our kids. He would take my Renualt 16 from school, park in the waiting line at John's Texaco for my 5 gallons or whatever the ration was at the time. I had certainly had it with the energy crisis, after having had to travel to Maine, over past the White Mountains, with three babies and a can of gas i nthe back - just in case. Warm weather and the racing season was a welcome relief.

Dragon Family Photo

by Bob Doyle

Beaver poses with a

checkered flag with the brand new home built

Chevelle. Later that day [below] he'd have a real checkered flag win.

Courtesy of Rich

Palmer

The car, to be a 1964 Chevelle, had a very impressive crew -with crew chief Norm Potvin, Doug McLeod, Randy Cary, and more working for local owners Paul Robar and Herb Everest. The car would exceed expectations, given that some of the others [including brother, Bob Dragon] were sporting professionally – built chassis' s from down South from such as Bobby Allison and Banjo Matthews.

What I most fondly recall is that Beaver was surprise winner of the first two features of the season with that Chevelle. Very unexpected. But the big story here is what that Chevelle [and every other of the numerous other quality late models on the Northern NASCAR Tour that year] would be facing in terms of a schedule that could best be described as a little psychotic.

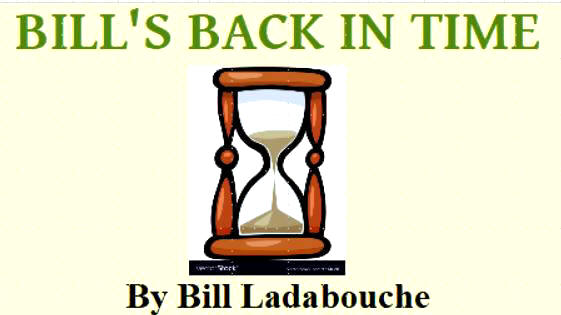

Courtesy of Mark Signor

There it is, in all its

glory ! That crazy schedule from the first

part of the 1973 season. Below – The cars' conditions often gave

mute testimony to the strain of the circuit. Tom Tiller [7]] was

fussy about his car's appearance. Despite having more than

one car, he couldn't keep up with the damage.

Courtesy of Chris Companion

1973 was a crossroads for two types of racing in the Northeast. That showcase of modified racing – the All Star Stock Car Racing League, having thrilled crowds since 1967 would be folding its tents at the end of the season, the victim of both the energy crisis and health problems with its principal leaders. Meanwhile, late model sportsman racing would start on a meteoric rise in the person of the Northern NASCAR circuit.

Ironically, Catamount was at the epicenter of the late model sportsman surge of the early 1970's; and yet, it also had an All Star League team [which, in fact, won the ASL championship in that, the League's final year]. Except for hosting a League race in 1973, the track pretty much ignored the League. It had an “all star” race that season in which fans chose their favorite late model drivers for a special race.

Ladabouche

Collection

Jerry Cook and Ron Narducci, two of the most

consistent attendees

of All Star League races, won the title for Catamount in 1973. I

Doubt that many Catamount regulars had any idea of it. Below – Cook

at a Catamount ASL show around 1972. Notice the collapsed

Chevron station in the background, having just ruined about

a week or so ago by guys sitting on it to watch the races.

Ladabouche Photo

Northern NASCAR had begun with a small circle of Catamount Stadium and Thunder Road, with a loose connection with Airborne Speedway by 1972. The tour was attracting new teams – particularly from Massachusetts, by the dozen. Teams could see the exposure the tour was getting and the three track situation gave big opportunity for points and prize money. Airborne was running Friday nights and Catamount had Saturdays; I believe T Road was running Thursday nights at the time.

And so it was that, despite the lingering energy crunch, the oout - of - sight All Star League campaign that would lead to the Catamount tyeam winning the last League title, and all of the other distractions that could have come up, Northern NASCAR took off on what would become perhaps the bravest attempt at an over - inflated weekly racing schedule in the history of the sport.

Lynch Photo

Modified racing was far

from on the decline anywhere but northern

New England. Richie Evans' coupe shows the wear and tear of

constant touring. But they had a little more choice in where and how

much they ran. Below – The wearing, but high profile Northern NASCAR circuit

gave

rise to many new careers like that of a very young Robbie Crouch.

Courtesy of Jim Watson

Ken Squier's publicity mill was getting the most out of the high quality competition among his old Flying Tiger regulars like the Dragon brothers, Tom Tiller, Moe Dubois, Bob Giroux, Stub Fadden, and more. To this, was added the return of the Canadians, many of whom had been dominant at all three tracks in the modified and sportsman coupe days: Jean – Paul Cabana and Andre Manny now came with a number of younger Quebec late model specialists such as Jacques Ste-Marie and J.C Gratton.

The Massachusetts invaders were led by John Rosati, of Agawam with his pair of 1967 Fred Rosner – built Fords and young Joey Kourafas who had taken over the wheel of Bob Curtiss' low budget but potent 25 MA. The Bay State contingent was large, and growing by leaps and bounds and included four – time NASCAR National Sportsman Champion Rene Charland . To round out, a fairly strong group came out of northern New York [around Airborne] that included 1961 NASCAR National Co- Champion Dick Nephew and several others.

Ladabouche Photo

Showy teams like John Rosati [above] and

returning Canadian

champion Jean-Paul Cabana helped attract cars and fans to

the Northern NASCAR circuit. The second car would become

a thing of amazement, going through Cabana, Don Bevins, Jack Dubrul,

Austin Dickerman [for Ed Foley], and Bob Ellis before heading

out to pasture.

Ladabouche Photo

By 1973, other tracks wanted in on what was happening with the Northern NASCAR tour. C.J. Richards and Devil's Bowl had jumped on board, with their Sunday running date. Then, in 1973, Squier added the new Canadian track at Sanair International Speedway – then known primarily for its impressive drag strip. The only night available for Sanair owner Jacques Guertin was Wednesday. So the fancy new Sanair track, named for a system of clearing the air in poultry barns, soldiered along with a midweek date.

So, now you had a weekly grind like no other. Yes, many semi – professional drivers had run numerous times a week in modifieds [and some made a living doing it] but the difference here was the Northern NASCAR teams had NO choice, unless they didn't care about the tour points race. Their week began by a very long haul up to St Pie, Quebec to run on a perfectly flat one third mile track Guertin had built on the other side of the stands from the drag strip. The setup for this was a little like Airborne on Friday, but in between would come the quarter mile, highly banked Thunder Road.

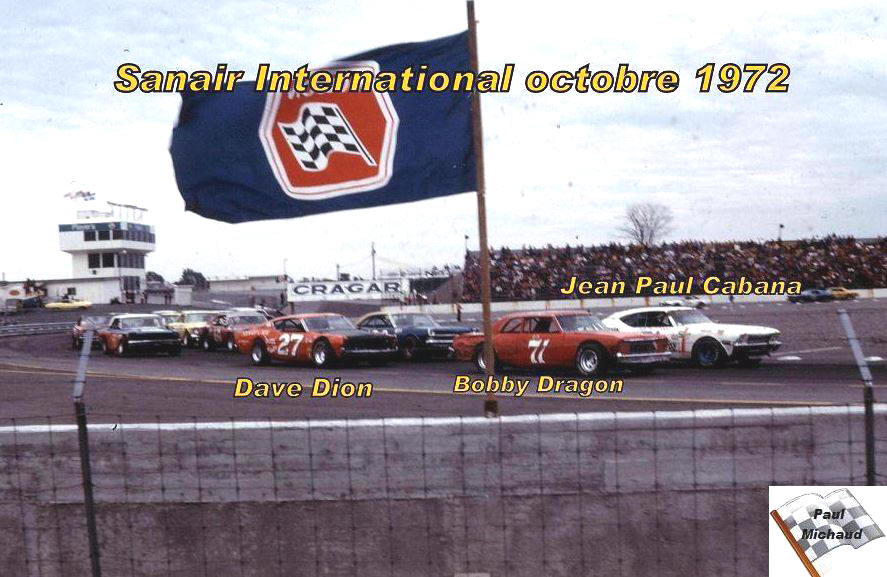

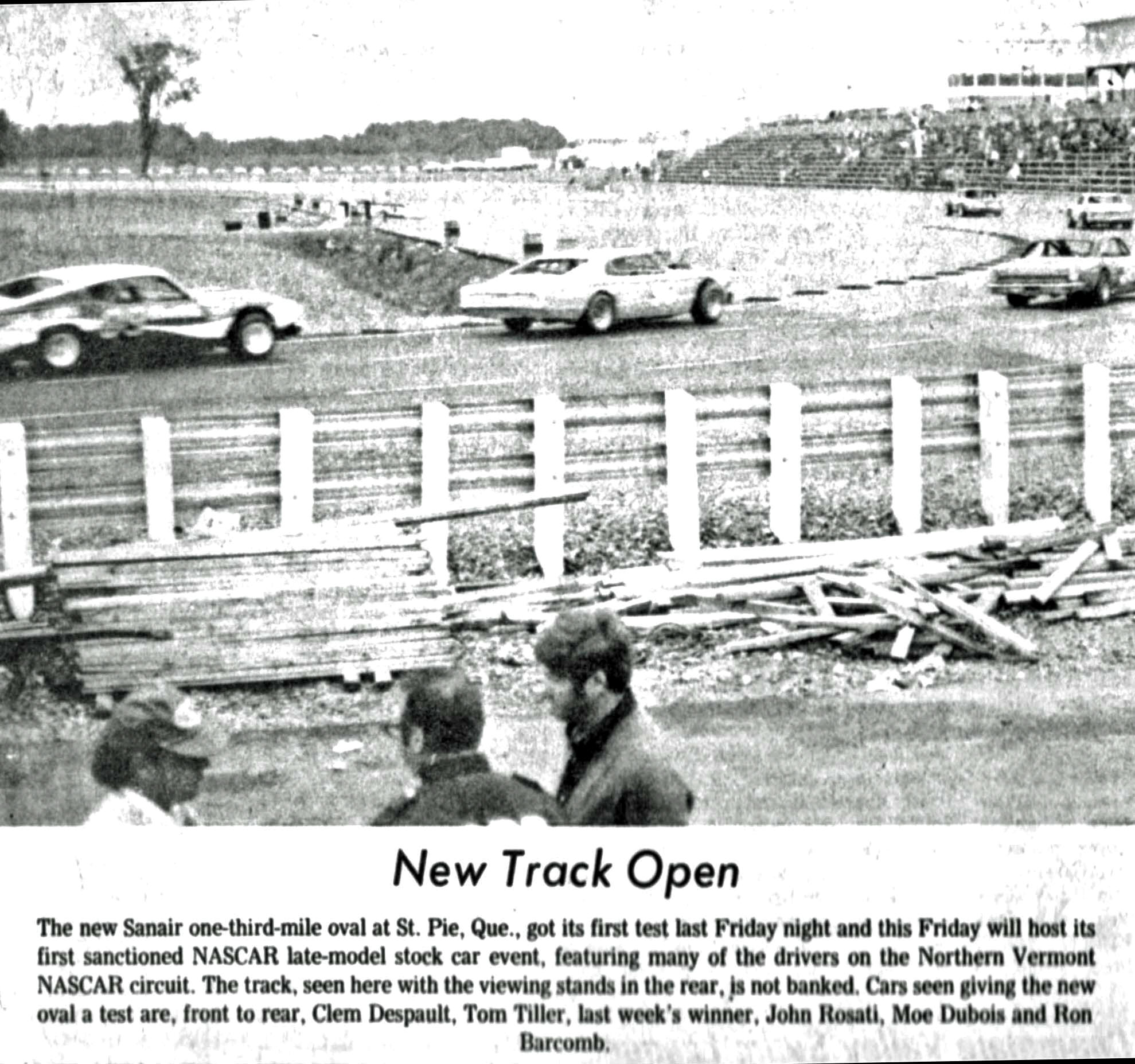

Paul Michaud

Photo

Northern NASCAR late models, led by Cabana and

Bob Dragon

prepare to go on the absolutely flat Sanair third mile. Pretty good crowd for a

Wednesday.

The tower served only the dragstrip. Below - This

shot is from Sanair's opening show in 1973.

Burlington Free

Press Photo via Wayne Bettis

So, Thursday night came with the tow into Barre, VT, in the center of Vermont. Settled into a natural bowl about the granite captial of the world, the track was, by now, 13 years old, poorly – lit, and a total opposite from Sanair. The track, with its wicked slanting front stretch wall called the Widowmaker, would inflict a lot of damage. Charland once catapulted up that wall and onto the lawn above twice in one season.

The following day meant either hauling all the way up to border, and crossing over to New York on the Champlain Bridge, or paying to take the Lake Champlain ferry, using a more expensive but more direct route to the old track in South Plattsburgh, NY. Airborne Park Speedway's 18 year – old paved track was coming apart. Most teams had a crew member responsible for removing the pieces of asphalt from the back seat of the car after each race. The old lighting was so bad many teams had colored lights on the roof so that crews in the mosquito – ridden pits could tell which car was theirs.

Free Press Photo

via Wayne Bettis

Rene Charland, on his way up the Widowmaker for

the second

time that season at Thunder Road. Below – Danny Bridges was

the low buck, but successful home track hero from Airborne.

Courtesy of Dan

Nolin

Airborne, established in 1954, was the oldest track by far. The long, paper clip shaped track was close to totally flat. Beaver Dragon had always held the place as his favorite track and performed brilliantly there. Local heroes like Nephew, Billy Branham, Bernie Griffith, Mackie Miller, and others were tougher competition there due to their familiarity with the cranky old oval.

Saturday night meant recrossing the lake and heading to Catamount Stadium, the headliner of the tour. The state of the art track, built in 1965, was a third mile like Sanair, but quite well banked. Ken Squier said, in an interview in 2107, that it had been designed after Old Dominion Speedway in Virginia and was made for handling, not raw speed. Catamount usually also drew the largest fields – although – by the fourth night out of five, there was some equipment lost for the week by then.

Courtesy of Rich

Palmer

Bob Dragon stands with a sponsorless Chevelle at

Catamount in

1973. After a few of his 20+ wins, the Howard Bank arrived on

his car. Below – A full grandstand of fans awaits the feature green at

for a full field of cars at Catamount in 1973.

Denis LaChance

Photo

Sunday nights were when Devil's Bowl Speedway had almost always run; but that was mostly to draw cars from such dirt tracks as Fonda and Lebanon Valley [and it worked]. Now paved, a very unpopular act with the locals in the area, the Bowl was a bit oddly configured and mildly banked. I always felt the turns were quite sharp. C.J. Richards often got the short end of the stick as far as the Tour was considered. There was a lot of attrition by the fifth day of the week. The Bowl would get fewer and often beat up cars to present to a crowd that was already angry because the track was no longer dirt. Richards was surviving this time by drawing serious tour fans who would attend as many shows as they could.

Another shaft job Richards got was that sometimes, Thunder Road was given Sunday afternoon to run its shows. Then the teams had to throw everything in the hauler and make a vexing trip down Interstate 89 and then west, over Killington mountain to get to Devil's Bowl, which was right on Vermont's western border. Mike Richards relates the story of visiting star Tiny Lund whose harried crew rushed so much to get down to West Haven that they lost the jack in the middle of the road somewhere outside the hamlet of Stockbridge, just east of Rutland. They didn't even realize it.

Devil's Bowl

Facebook Page

A drivers' confab at one of the Devil's Bowl

programs in 1973. Dan Perez [left], with

Danny Bridges and D Bowl regulars Vince Quenneville, Sr., and

Johnny Bruno. Only Quenneville ever had much success on the circuit.

Below – D Bowl hometown favorite Bob Eliis did win Rookie of the Year

for Northern NASCAR in 1973 despite a late start in the season.

Courtesy of Ron

Rondeau

So unusual and illogical was this Squier brainchild, Stock Car Racing magazine did a feature article [none too complimentary] on the circuit in the middle of the season. The premise of the article seemed to be that it was chaotic and ridiculous. The cars that did make most of the races got to looking worse and worse. Lucky teams like Rosati, Tom Tiller, Ron Barcomb, and a few others had more than one car. The second car served sometimes to bail out the driver when the primary ride wads bent; but, it also sometimes served as a field filler when the fields were dwindling and there was an idle driver looking for a ride.

The Northern NASCAR circuit would result in three of its drivers landing in the top ten of NASCAR National Sportsman points: Cabana, 7th; Bob Dragon, 9th; and Beaver Dragon 10th. Dave Dion would finish 17th. The Southerners were still way ahead technologically and had more opportunities for more big point races that those in the North. Sanair had dropped out of the circuit before the season was half done and its drivers did not appear in NASCAR points.

Courtesy of Mr.

Chevy Black

Ron Barcomb uses his Fairlane 500 backup car here

as he pursues

Cabana in a 1973 circuit race. John Rosati, who had a backup of his own,

runs third. Below – Bob Dragon won the title with only one, very effective

Allison chassis Chevelle. This photo shows the effects of the

grueling schedule on the car, now having a good sponsor.

Bob Mackey Photo via Dave Brown

Bob Dragon won the title at Thunder Road by a good margin while Dion [who loved T Road the way Beaver loved Airborne] edged out Beaver by 20 points. Surprise fourth was low budget South Plattsburgh , NY driver Danny Bridges. Airborne did not officially rank in NASCAR points either, but I believe Beaver Dragon won there. Catamount was won by Jean – Paul Cabana [as he so often did] with the Dragons in close pursuit. Again, Bridges finished strong as did T Road hero Ronnie Marvin, who chose not to run at all the tracks. Devil's Bowl did not show up in NASCAR points.

Had the those other three tracks had appeared in national points, I feel that Cabana, the Dragons, and others would have finished right up there with the Southerners in the final points. Bob Dragon would win the Vermont state title in the NASCAR record book handily, with Beaver second. Dave Dion, Bridges, and Marvin rounded out the top five. Ironically, Devil's Bowl's Chargers appeared in the NASCAR hobby points that year along with Catamount and T Road, but not Airborne [which was running with many of the same drivers]. Airborne and the Bowl were both C.J. Richards operations, so why one track's hobbies and not the others appear is beyond me.

Courtesy of Andy Boright

Huge, intimidating Ronnie

Marvin, The Bethlehem Bombshell,

dwarfs his car on the track at Catamount in 1973. Below – Former

Norwood Arena standout Dave Dion came out of Hudson, NH to

be a superstar with Northern NASCAR.

Ladabouche Collection

I do know that it was quite a year for all of us. At that time, I was running a

sign painting business and the strain of the schedule on the cars' bodies gave

me a lot of work. By 1974, Airborne and Devil's Bowl would be bowing out. Squier

and [by then] Tom Curley would embark on another tour concept wherein each track

would not be running ever week. Many other tracks were brought in for single

race appearances during what would become the “beer tours” – a number of seasons

that three different beer companies [Molson, Stroh's,. and Coors] took turns

giving extensive sponsor support. It worked a lot better and that idea still

lives on today with the ACT tour.

A and A Ward

Photo

The tortuous 1973 schedule afforded lessons and

exposure that led

to NASCAR North, a hugely successful touring series in the mid 1980's.

Please email me if you have any photos to lend me or information and corrections I could benefit from. Please do not submit anything you are not willing to allow me to use on my website - and thanks. Email is: wladabou@comcast.net . For those who still don’t like computers - my regular address is: Bill Ladabouche, 23 York Street,Swanton, Vermont 05488.

AS ALWAYS, DON’T FORGET TO CHECK OUT THE

REST OF MY WEBSITE

www.catamountstadium.com

Return to the Main Page

Return to the Main News Page

Return to the All Links Page

Return to the Weekly Blog Links Page